The attractive force which holds various constituents (atoms, ions, etc.) together in different chemical species is called a chemical bond.

Every system tries to be more stable and bonding is nature’s way of lowering the energy of the system to attain stability.

To explain the chemical bonding following 4 approaches have been accepted.

Kössel-Lewis approach

Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) Theory

Valence Bond (VB) Theory

Molecular Orbital (MO) Theory

Kössel-Lewis Approach to Chemical Bonding

Lewis postulated that atoms achieve the stable octet when they are linked by chemical bonds.

In the case of sodium and chlorine, this can happen by the transfer of an electron from sodium to chlorine thereby giving the Na+ and Cl– ions.

In the case of other molecules like Cl2, H2, F2, etc., the bond is formed by the sharing of a pair of electrons between the atoms. In the process each atom attains a stable outer octet of electrons.

Octet Rule: (electronic theory of chemical bonding)

Atoms can combine either by transfer of valence electrons from one atom to another (gaining or losing) or by sharing of valence electrons in order to have an octet in their valence shells.

In the formation of a molecule, only the valence electrons take part in chemical combination.

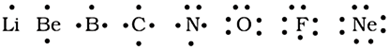

Lewis introduced simple notations to represent valence electrons in an atom. These notations are called Lewis symbols.

For example, the Lewis symbols for the elements of second period are as under:

Significance of Lewis Symbols:

The number of dots around the symbol represents the number of valence electrons. This number of valence electrons helps to calculate the common or group valence of the element.

Group valence of the elements is generally either equal to the number of dots in Lewis symbols or 8 minus the number of dots (valence electrons).

The bond formed, as a result of the electrostatic attraction between the positive and negative ions is termed as the electrovalent bond. The electrovalence is thus equal to the number of unit charge(s) on the ion.

Thus, calcium is assigned a positive electrovalence of two, while chlorine a negative electrovalence of one.

When two atoms share one electron pair they are said to be joined by a single covalent bond.

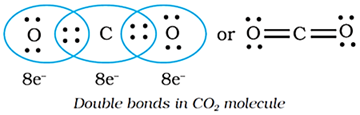

In the formation of multiple bonds, sharing of more than one electron pair between two atoms takes place. If two atoms share two pairs of electrons, the covalent bond between them is called a double bond.

E.g., in the carbon dioxide molecule, we have two double bonds between the carbon and oxygen atoms.

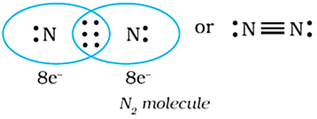

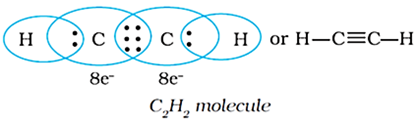

When combining atoms share three electron pairs as in the case of two nitrogen atoms in the N2 molecule and the two carbon atoms in the ethyne molecule, a triple bond is formed.

The Lewis dot structures provide a picture of bonding in molecules and ions in terms of the shared pairs of electrons and the octet rule.

Steps to write Lewis dot structures:

• The total number of electrons required for writing the structures are obtained by adding the valence electrons of the combining atoms. For example, in the CH4 molecule there are eight valence electrons available for bonding (4 from carbon and 4 from the four hydrogen atoms).

• For anions, each negative charge would mean addition of one electron. E.g., in CO32– ion, the two negative charges indicate that there are two additional electrons than those provided by the neutral atoms.

• For cations, each positive charge would result in subtraction of one electron from the total number of valence electrons. E.g., in NH4+ ion, one positive charge indicates the loss of one electron from the group of neutral atoms.

• Knowing the chemical symbols of the combining atoms and having knowledge of the skeletal structure of the compound (known or guessed intelligently), it is easy to distribute the total number of electrons as bonding shared pairs between the atoms in proportion to the total bonds.

• In general, the least electronegative atom occupies the central position in the molecule/ion. For example, in the NF3 and CO32–, nitrogen and carbon are the central atoms whereas fluorine and oxygen occupy the terminal positions.

• After accounting for the shared pairs of electrons for single bonds, the remaining electron pairs are either utilized for multiple bonding or remain as the form of lone pairs. The basic requirement being that each bonded atom gets an octet of electrons.

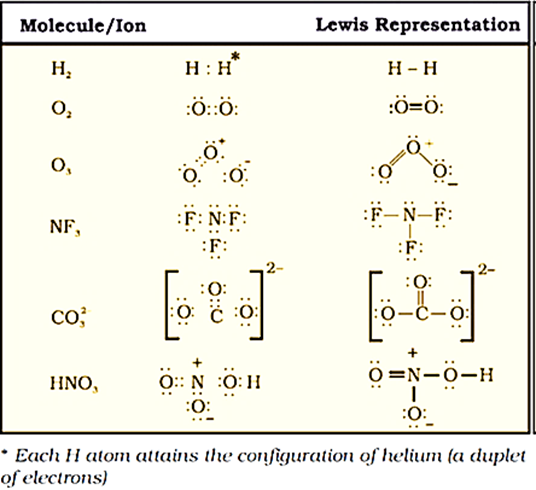

Lewis representations of a few molecules/ions

Formal Charge:

In case of polyatomic ions or molecules, the net charge is possessed by the ion/molecule as a whole and not by a particular atom.

It is, however, feasible to assign a formal charge on each atom.

The formal charge of an atom in a polyatomic molecule or ion may be defined as the difference between the number of valence electrons of that atom in an isolated or free state and the number of electrons assigned to that atom in the Lewis structure.

It is expressed as:

The Lewis structure of O3 may be drawn as:

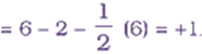

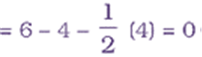

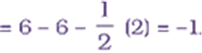

The central O atom marked 1 has formal charge

The end O atom marked 2 has formal charge

The end O atom marked 3 has formal charge

Hence, we represent O3 along with the formal charges as follows:

Formal charges do not indicate real charge separation within the molecule. Indicating the charges on the atoms in the Lewis structure only helps in keeping track of the valence electrons in the molecule.

Generally, the lowest energy structure is the one with the smallest formal charges on the atoms. The formal charge is a factor based on a pure covalent view of bonding in which electron pairs are shared equally by neighbouring atoms.

Formal charges help in the selection of the lowest energy structure from a number of possible Lewis structures for a given species.

Limitations of the Octet Rule:

The octet rule is not universal.

It applies mainly to the second period elements of the periodic table.

There are 6 types of exceptions to the octet rule.

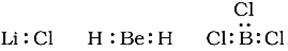

(i) The incomplete octet of the central atom:

In some compounds, the number of electrons surrounding the central atom is less than eight. This is especially the case with elements having less than four valence electrons.

Examples are LiCl, BeH2 and BCl3.

Li, Be and B have 1, 2 and 3 valence electrons only. Some other such compounds are AlCl3 and BF3.

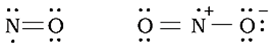

(ii) Odd-electron molecules:

In molecules with an odd number of electrons like nitric oxide, NO and nitrogen dioxide, NO2, the octet rule is not satisfied for all the atoms

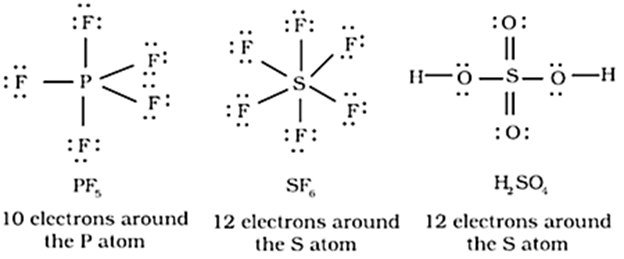

(iii) The expanded octet:

Elements in and beyond the third period of the periodic table have, apart from 3s and 3p orbitals, 3d orbitals also available for bonding.

In a number of compounds of these elements there are more than eight valence electrons around the central atom.

This is termed as the expanded octet.

Obviously, the octet rule does not apply in such cases.

Some of the examples of such compounds are: PF5, SF6, H2SO4 and a number of coordination compounds.

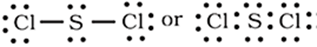

Sulphur also forms many compounds in which the octet rule is obeyed.

In sulphur dichloride, the S atom has an octet of electrons around it.

(iv) Chemical Inertness of Noble gases

It is clear that octet rule is based upon the chemical inertness of noble gases. However, some noble gases (for example xenon and krypton) also combine with oxygen and fluorine to form a number of compounds like XeF2, KrF2, XeOF2 etc.

(v) Shape of Molecule not defined

This theory does not account for the shape of molecules.

(vi) Energy of Molecule not defined

It does not explain the relative stability of the molecules being totally silent about the energy of a molecule.

Kössel And Lewis Theory of Ionic or Electrovalent Bond:

From the Kössel and Lewis treatment of the formation of an ionic bond, it follows that the formation of ionic compounds would primarily depend upon,

• The ease of formation of the positive and negative ions from the respective neutral atoms;

• The arrangement of the positive and negative ions in the solid, that is, the lattice of the crystalline compound.

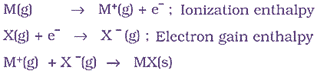

The formation of a positive ion involves ionization, i.e., removal of electron(s) from the neutral atom.

The formation of a negative ion involves the addition of electron(s) to the neutral atom.

Electron gain enthalpy is the enthalpy change, when a gas phase atom in its ground state gains an electron. The electron gain process may be exothermic or endothermic.

The ionization enthalpy is the enthalpy change, when a gas phase atom in its ground state loses a valence electron. The ionization enthalpy is always endothermic.

Electron affinity is the negative of the energy change accompanying electron gain.

Ionic bonds will be formed more easily between elements with comparatively low ionization enthalpies and elements with comparatively high negative value of electron gain enthalpy.

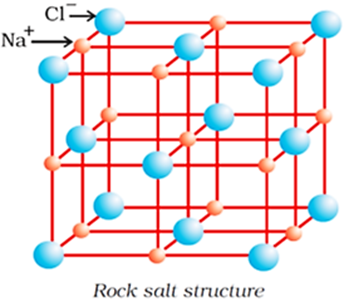

Ionic compounds in the crystalline state consist of orderly three-dimensional arrangements of cations and anions held together by coulombic interaction energies.

In ionic solids, the sum of the electron gain enthalpy and the ionization enthalpy may be positive but still the crystal structure gets stabilized due to the energy released in the formation of the crystal lattice.

For example: the ionization enthalpy for Na+(g) formation from Na(g) is 495.8 kJ mol–1; while the electron gain enthalpy for the change

Cl(g) + e– → Cl– (g)

is, – 348.7 kJ mol–1 only.

The sum of the two, 147.1 kJ mol-1 is more than compensated for by the enthalpy of lattice formation of NaCl(s) (–788 kJ mol–1).

Therefore, the energy released in the processes is more than the energy absorbed.

Thus, a qualitative measure of the stability of an ionic compound is provided by its enthalpy of lattice formation and not simply by achieving octet of electrons around the ionic species in gaseous state.

The Lattice Enthalpy of an ionic solid is defined as the energy required to completely separate one mole of a solid ionic compound into gaseous constituent ions.

For example, the lattice enthalpy of NaCl is 788 kJ mol–1. This means that 788 kJ of energy is required to separate one mole of solid NaCl into one mole of Na+ (g) and one mole of Cl– (g) to an infinite distance.

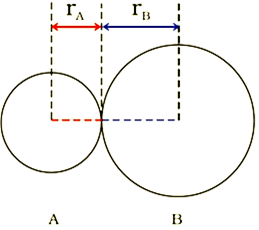

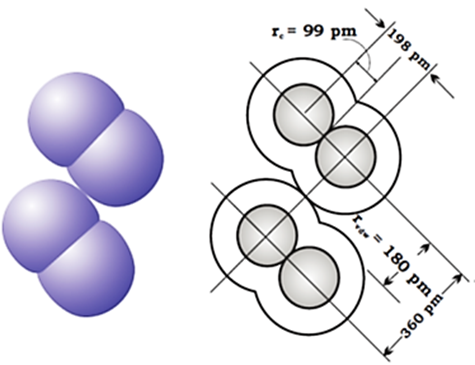

Bond length is defined as the equilibrium distance between the nuclei of two bonded atoms in a molecule.

The covalent radius is measured approximately as the radius of an atom’s core which is in contact with the core of an adjacent atom in a bonded situation.

R = rA + rB

(R is the bond length and rA and rB are the covalent radii of atoms A and B respectively)

The van der Waals radius represents the overall size of the atom which includes its valence shell in a non-bonded situation.

The van der Waals radius is half of the distance between two similar atoms in separate molecules in a solid.

rvdw and rc are van der Waals and covalent radii respectively

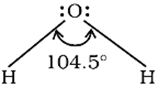

It is defined as the angle between the orbitals containing bonding electron pairs around the central atom in a molecule/complex ion.

It is defined as the amount of energy required to break one mole of bonds of a particular type between two atoms in a gaseous state.

The unit of bond enthalpy is kJ mol–1. For example, the H – H bond enthalpy in hydrogen molecule is 435.8 kJ mol–1.

Larger the bond dissociation enthalpy, stronger will be the bond in the molecule.

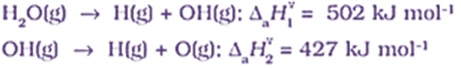

In case of H2O molecule, the enthalpy needed to break the two O – H bonds is not the same.

The difference in the ΔaHV value shows that the second O – H bond undergoes some change because of changed chemical environment.

This is the reason for some difference in energy of the same O – H bond in different molecules like C2H5OH (ethanol) and water.

Therefore, in polyatomic molecules the term mean or average bond enthalpy is used.

For water,

In the Lewis description of covalent bond, the Bond Order is given by the number of bonds between the two atoms in a molecule.

Isoelectronic molecules and ions have identical bond orders; for example, F2 and O22– have bond order 1. N2, CO and NO+ have bond order 3.

With increase in bond order, bond enthalpy increases and bond length decreases.

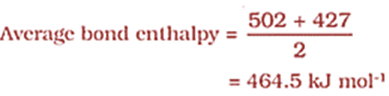

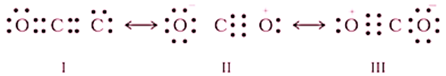

Sometimes a single Lewis structure is inadequate for the representation of a molecule in conformity with its experimentally determined parameters. For example, the ozone, O3 molecule can be equally represented by the structures I and II shown below:

(structures I and II represent the two canonical forms while the structure III is the resonance hybrid)

The normal O–O and O=O bond lengths are 148 pm and 121 pm respectively. Experimentally determined oxygen-oxygen bond lengths in the O3 molecule are same (128 pm). Thus, the oxygen-oxygen bonds in the O3 molecule are intermediate between a double and a single bond. Obviously, this cannot be represented by either of the two Lewis structures shown above.

According to the concept of resonance, whenever a single Lewis structure cannot describe a molecule accurately, a number of structures with similar energy, positions of nuclei, bonding and non-bonding pairs of electrons are taken as the canonical structures of the hybrid which describes the molecule accurately.

Thus, for O3, the two structures shown above constitute the canonical structures or resonance structures and their hybrid i.e., the III structure represents the structure of O3 more accurately. This is also called resonance hybrid. Resonance is represented by a double headed arrow.

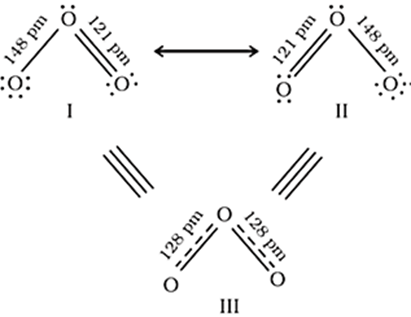

The resonance hybrid of carbonate ion is described as the CO32– canonical forms I, II, and III shown below.

The resonance hybrid of carbonate ion is described as the CO2 canonical forms I, II, and III shown below.

· Resonance stabilizes the molecule as the energy of the resonance hybrid is less than the energy of any single canonical structure.

· Resonance averages the bond characteristics as a whole. Thus, the energy of the O3 resonance hybrid is lower than either of the two canonical forms I and II.

· The canonical forms have no real existence.

· The molecule does not exist for a certain fraction of time in one canonical form and for other fractions of time in other canonical forms.

· There is no such equilibrium between the canonical forms as we have between tautomeric forms (keto and enol) in tautomerism.

· The molecule as such has a single structure which is the resonance hybrid of the canonical forms and which cannot as such be depicted by a single Lewis structure.

When covalent bond is formed between two similar atoms, for example in H2, O2, Cl2, N2 or F2, the shared pair of electrons is equally attracted by the two atoms. As a result, electron pair is situated exactly between the two identical nuclei. The bond so formed is called nonpolar covalent bond.

Contrary to this in case of a heteronuclear molecule like HF, the shared electron pair between the two atoms gets displaced more towards fluorine since the electronegativity of fluorine is far greater than that of hydrogen. The resultant covalent bond is a polar covalent bond.

As a result of polarisation, the molecule possesses the dipole moment (depicted below) which can be defined as the product of the magnitude of the charge and the distance between the centres of positive and negative charge. It is usually designated by a Greek letter ‘μ’. Mathematically, it is expressed as follows:

Dipole moment (μ) = charge (Q) × distance of separation (r)

μ = Q × r

Dipole moment is usually expressed in Debye units (D).

The conversion factor is

1 D = 3.33564 × 10–30 C m

where C is coulomb and m is meter.

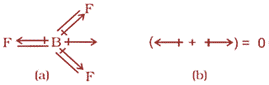

The dipole moment in case of BeF2 is zero. This is because the two equal bond dipoles point in opposite directions and cancel the effect of each other.

In BF3, the dipole moment is zero although the B – F bonds are oriented at an angle of 120° to one another, the three bond moments give a net sum of zero as the resultant of any two is equal and opposite to the third.

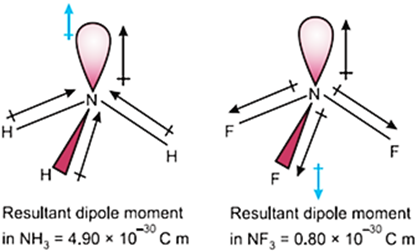

Dipole moment in NH3 and NF3 molecules:

Both the molecules have pyramidal shape with a lone pair of electrons on nitrogen atom. Although fluorine is more electronegative than nitrogen, the resultant dipole moment of NH3 (4.90 × 10–30 C m) is greater than that of NF3 (0.8 × 10–30 C m).

This is because, in case of NH3 the orbital dipole due to lone pair is in the same direction as the resultant dipole moment of the N – H bonds, whereas in NF3 the orbital dipole is in the direction opposite to the resultant dipole moment of the three N–F bonds. The orbital dipole because of lone pair decreases the effect of the resultant N – F bond moments, which results in the low dipole moment of NF3.

All covalent bonds have some partial ionic character, and all ionic bonds have partial covalent character.

The partial covalent character of ionic bonds was discussed by Fajans in terms of the following rules:

· The smaller the size of the cation and the larger the size of the anion, the greater the covalent character of an ionic bond.

· The greater the charge on the cation, the greater the covalent character of the ionic bond.

· For cations of the same size and charge, the one, with electronic configuration

(n-1)dnnso, typical

of transition metals, is more polarising than the one with a noble gas configuration, ns2 np6,

typical of alkali and alkaline earth metal cations.

The polarising power of the cation, the polarisability of the anion and the extent of distortion (polarisation) of anion are the factors, which determine the per cent covalent character of the ionic bond.

The Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) Theory

Lewis concept is unable to explain the shapes of molecules.

VSEPR theory provides a simple procedure to predict the shapes of covalent molecules.

VSEPR theory based on the repulsive interactions of the electron pairs in the valence shell of the atoms.

The main postulates of VSEPR theory are as follows:

· The shape of a molecule depends upon the number of valence shell electron pairs (bonded or non-bonded) around the central atom.

· Pairs of electrons in the valence shell repel one another since their electron clouds are negatively charged.

· These pairs of electrons tend to occupy such positions in space that minimize repulsion and thus maximise distance between them.

· The valence shell is taken as a sphere with the electron pairs localising on the spherical surface at maximum distance from one another.

· A multiple bond is treated as if it is a single electron pair and the two or three electron pairs of a multiple bond are treated as a single super pair.

· Where two or more resonance structures can represent a molecule, the VSEPR model is applicable to any such structure.

The repulsive interaction of electron pairs decrease in the order:

lp – lp > lp – bp > bp – bp

where,

lp: Lone pair, bp: Bond pair

For the prediction of geometrical shapes of molecules with the help of VSEPR theory, it is convenient to divide molecules into two categories as

(i) molecules in which the central atom has no lone pair.

(ii) molecules in which the central atom has one or more lone pairs.

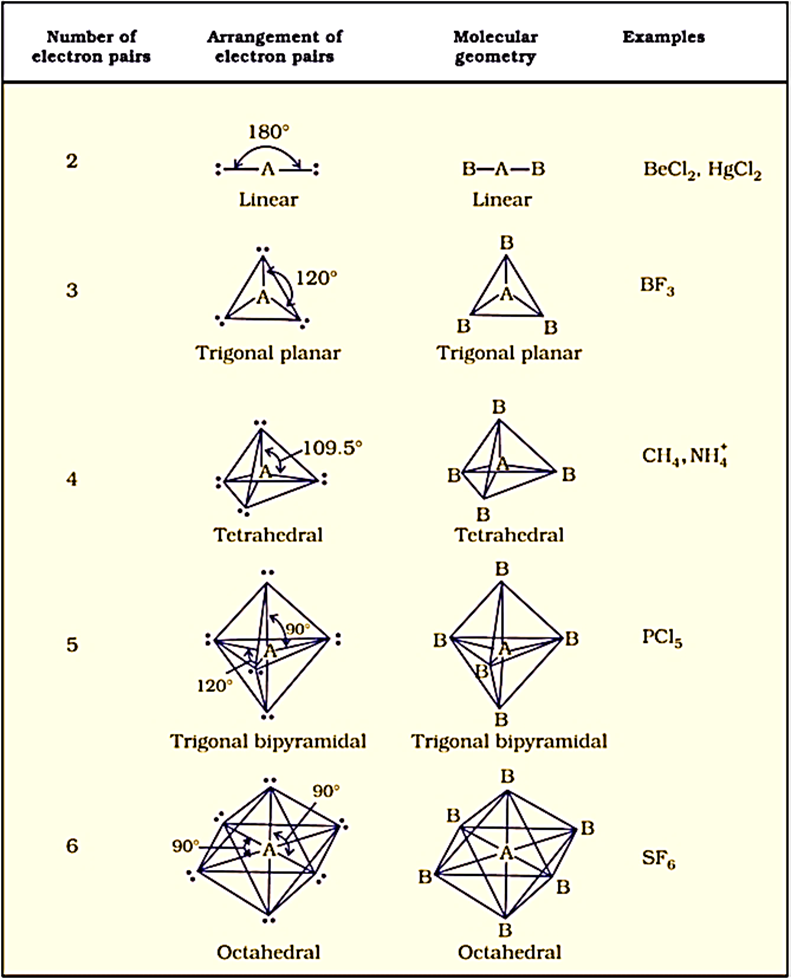

(The shapes of molecules in which central atom has no lone pair)

Table below shows the arrangement of electron pairs about a central atom A (without any lone pairs) and geometries of some molecules/ions of the type AB.

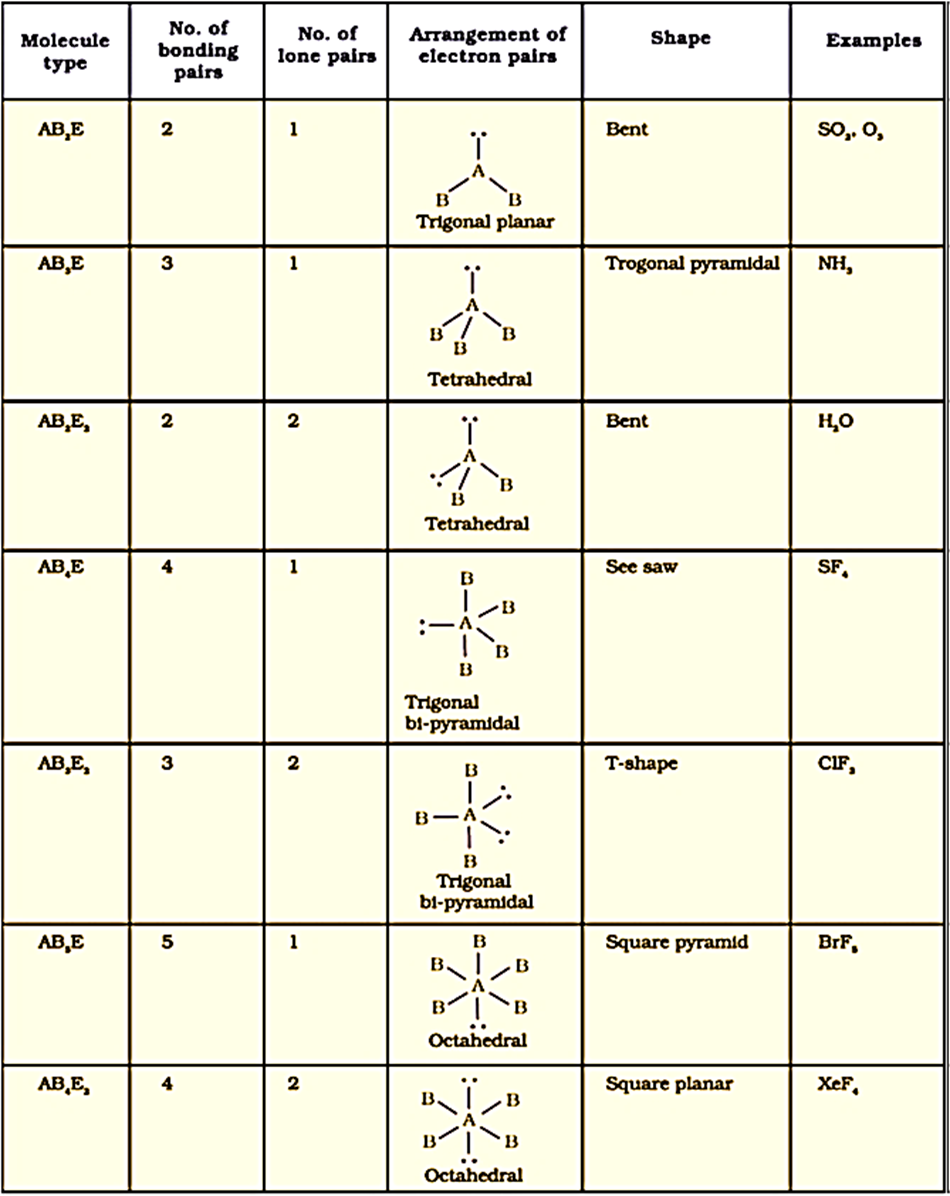

Table below shows shapes of some simple molecules and ions in which the central atom has one or more lone pairs.

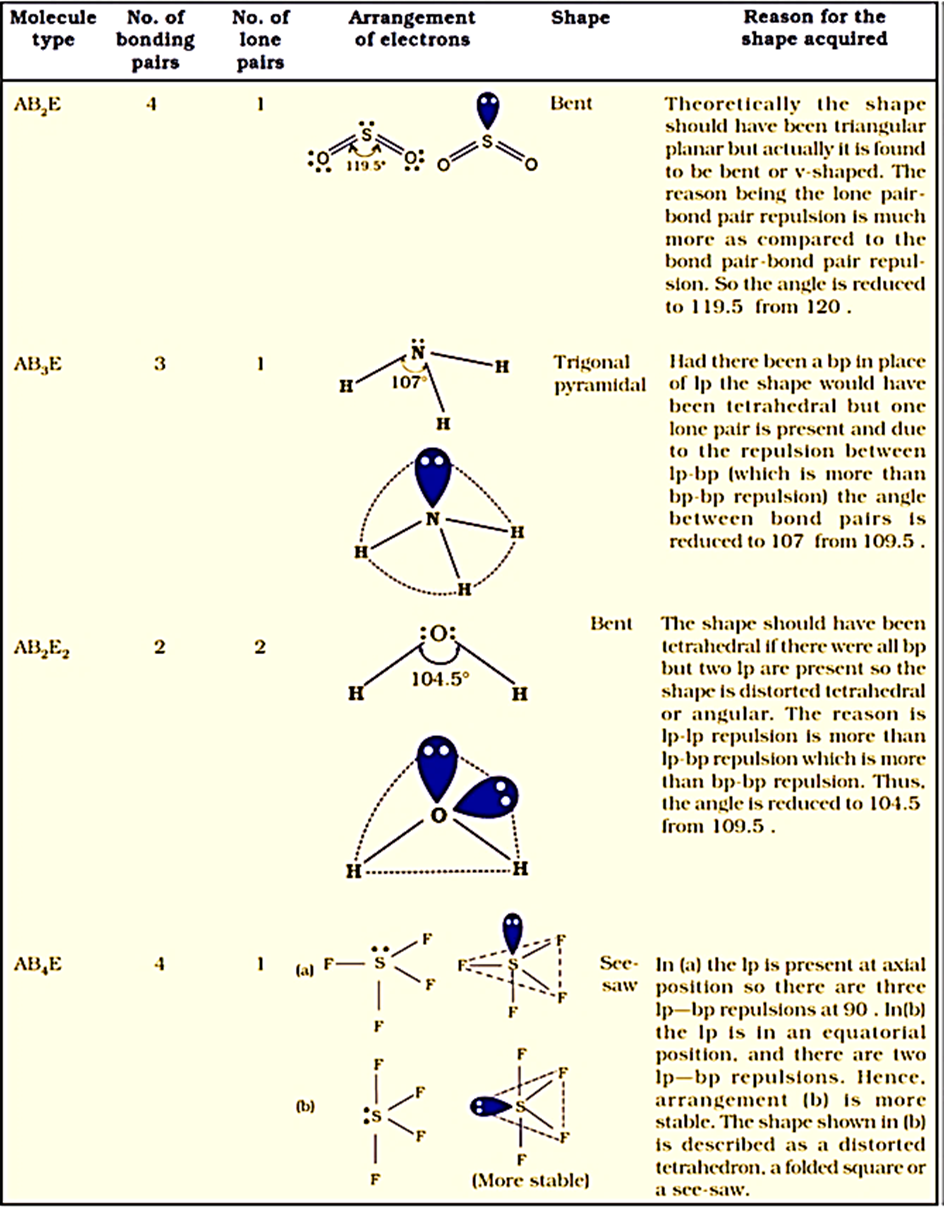

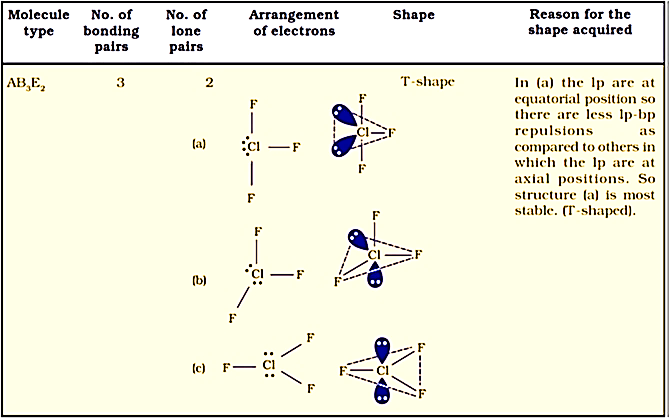

Table below explains the reasons for the distortions in the geometry of the molecule.

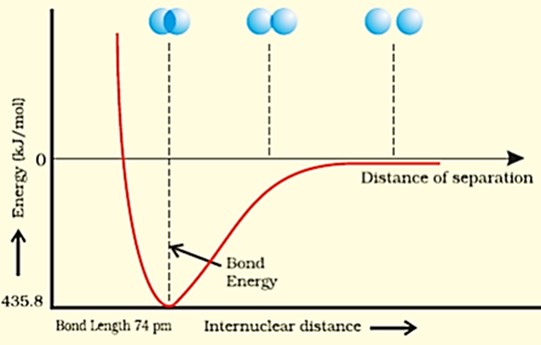

Consider two hydrogen atoms A and B approaching each other having nuclei NA and NB and electrons present in them are represented by eA and eB. When the two atoms are at large distance from each other, there is no interaction between them. As these two atoms approach each other, new attractive and repulsive forces begin to operate.

Attractive forces arise between:

(i) nucleus of one atom and its own electron that is NA – eA and NB – eB.

(ii) nucleus of one atom and electron of other atom i.e., NA – eB, NB – eA.

Similarly, repulsive forces arise between

(i) electrons of two atoms like eA – eB.

(ii) nuclei of two atoms NA – NB.

Attractive forces tend to bring the two atoms close to each other whereas repulsive forces tend to push them apart.

Experimentally it has been found that the magnitude of new attractive force is more than the new repulsive forces. As a result, two atoms approach each other and potential energy decreases. Ultimately a stage is reached where the net force of attraction balances the force of repulsion and system acquires minimum energy. At this stage two hydrogen atoms are said to be bonded together to form a stable molecule having the bond length of 74 pm.

Since the energy gets released when the bond is formed between two hydrogen atoms, the hydrogen molecule is more stable than that of isolated hydrogen atoms. The energy so released is called as bond enthalpy, which is corresponding to minimum in the curve depicted in the figure below. Conversely, 435.8 kJ of energy is required to dissociate one mole of H2 molecule.

H2(g) + 435.8 kJ mol–1 → H(g) + H(g)

The valence bond theory explains the formation and directional properties of bonds in polyatomic molecules like CH4, NH3 and H2O, etc. in terms of overlap and hybridisation of atomic orbitals.

Types of Overlapping and Nature of Covalent Bonds:

The covalent bond may be classified into two types depending upon the types of overlapping:

(i) Sigma(σ) bond, and (ii) pi(π) bond

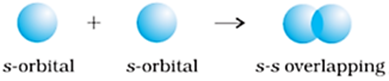

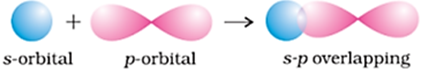

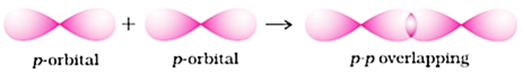

(i) Sigma(σ) bond: This type of covalent bond is formed by the end to end (hand-on) overlap of bonding orbitals along the internuclear axis. This is called as head on overlap or axial overlap. This can be formed by any one of the following types of combinations of atomic orbitals.

(a) s-s overlapping: In this case, there is overlap of two half-filled s-orbitals along the internuclear axis as shown below:

(b) s-p overlapping: This type of overlap occurs between half-filled s-orbitals of one atom and half-filled p-orbitals of another atom.

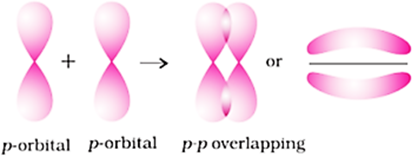

(c) p–p overlapping: This type of overlap takes place between half-filled p-orbitals of the two approaching atoms.

(ii) pi(π ) bond: In the formation of π bond the atomic orbitals overlap in such a way that their axes remain parallel to each other and perpendicular to the internuclear axis. The orbitals formed due to sidewise overlapping consists of two saucer type charged clouds above and below the plane of participating atoms.

Strength of Sigma and pi Bonds:

The strength of a bond depends upon the extent of overlapping. In case of sigma bond, the overlapping of orbitals takes place to a larger extent. Hence, σ-bond is stronger as compared to the pi bond where the extent of overlapping occurs to a smaller extent.

Further, it is important to note that pi bond between two atoms is formed in addition to a sigma bond. It is always present in the molecules containing multiple bond (double or triple bonds)

The atomic orbitals combine to form new set of equivalent orbitals known as hybrid orbitals. Unlike pure orbitals, the hybrid orbitals are used in bond formation.

The phenomenon is known as hybridisation which can be defined as the process of intermixing of the orbitals of slightly different energies so as to redistribute their energies, resulting in the formation of new set of orbitals of equivalent energies and shape.

For example, when one 2s and three 2p-orbitals of carbon hybridise, there is the formation of four new sp3 hybrid orbitals.

Salient features of hybridisation:

1. The number of hybrid orbitals is equal to the number of the atomic orbitals that get hybridised.

2. The hybridised orbitals are always equivalent in energy and shape.

3. The hybrid orbitals are more effective in forming stable bonds than the pure atomic orbitals.

4. These hybrid orbitals are directed in space in some preferred direction to have minimum repulsion between electron pairs and thus a stable arrangement. Therefore, the type of hybridisation indicates the geometry of the molecules.

Important conditions for hybridisation:

(i) The orbitals present in the valence shell of the atom are hybridised.

(ii) The orbitals undergoing hybridisation should have almost equal energy.

(iii) Promotion of electron is not essential condition prior to hybridisation.

(iv) It is not necessary that only half-filled orbitals participate in hybridisation. In some cases, even filled orbitals of valence shell take part in hybridisation.

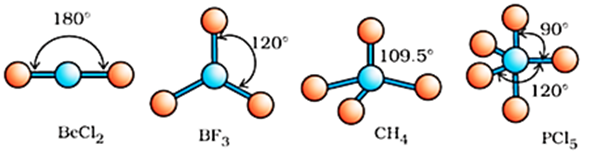

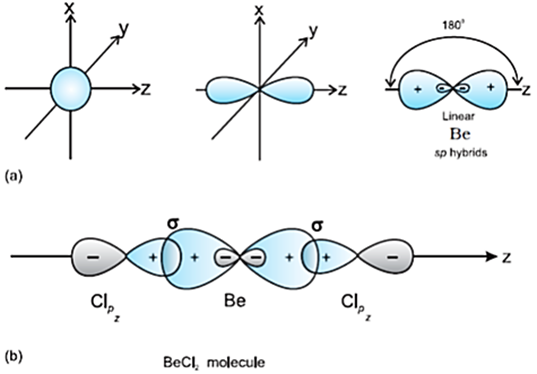

(i) sp hybridisation: It involves the mixing of one s and one p orbital resulting in the formation of two equivalent sp hybrid orbitals.

Each sp hybrid orbitals has 50% s-character and 50% p-character.

sp-hybridised molecule possesses linear geometry.

The two sp hybrids point in the opposite direction along the z-axis with projecting positive lobes and very small negative lobes, which provides more effective overlapping resulting in formation of stronger bonds.

Example of molecule having sp hybridisation

BeCl2: The ground state electronic configuration of Be is 1s2 2s2. In the exited state one of the 2s-electrons is promoted to vacant 2p orbital to account for its divalency.

One 2s and one 2p-orbitals get hybridised to form two sp hybridised orbitals. These two sp hybrid orbitals are oriented in opposite direction forming an angle of 180°. Each of the sp hybridised orbital overlaps with the 2p-orbital of chlorine axially and form two Be-Cl sigma bonds.

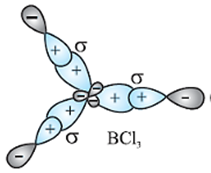

(ii) sp2 hybridisation: In this hybridisation there is involvement of one s and two p-orbitals in order to form three equivalent sp2 hybridised orbitals.

For example, in BCl3 molecule, the ground state electronic configuration of central boron atom is 1s2 2s2 2p1.

In the excited state, one of the 2s electrons is promoted to vacant 2p orbital as a result boron has three unpaired electrons.

These three orbitals (one 2s and two 2p) hybridise to form three sp2 hybrid orbitals.

The three hybrid orbitals so formed are oriented in a trigonal planar arrangement and overlap with 2p orbitals of chlorine to form three B-Cl bonds.

Therefore, in BCl3, the geometry is trigonal planar with Cl-B-Cl bond angle of 120°.

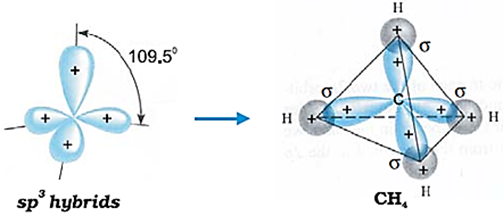

(iii) sp3 hybridisation: This type of hybridisation can be explained by taking the example of CH4 molecule in which there is mixing of one s-orbital and three p-orbitals of the valence shell to form four sp3 hybrid orbital of equivalent energies and shape.

There is 25% s-character and 75% p character in each sp3 hybrid orbital.

The four sp3 hybrid orbitals so formed are directed towards the four corners of the tetrahedron.

The angle between sp3 hybrid orbital is 109.5° as shown below.

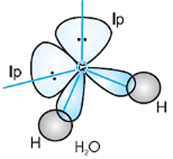

The structure of NH3 and H2O molecules can also be explained with the help of sp3 hybridisation.

In NH3, the valence shell (outer) electronic configuration of nitrogen in the ground state is 2s2 2px1 2py1 2pz1 having three unpaired electrons in the sp3 hybrid orbitals and a lone pair of electrons is present in the fourth one.

These three hybrid orbitals overlap with 1s orbitals of hydrogen atoms to form three N–H sigma bonds.

We know that the force of repulsion between a lone pair and a bond pair is more than the force of repulsion between two bond pairs of electrons.

The molecule thus gets distorted and the bond angle is reduced to 107° from 109.5°. The geometry of such a molecule will be pyramidal as shown in the figure below.

In case of H2O molecule, the four oxygen orbitals (one 2s and three 2p) undergo sp3 hybridisation forming four sp3 hybrid orbitals out of which two contain one electron each and the other two contain a pair of electrons.

These four sp3 hybrid orbitals acquire a tetrahedral geometry, with two corners occupied by hydrogen atoms while the other two by the lone pairs.

The bond angle in this case is reduced to 104.5° from 109.5° and the molecule thus acquires a V-shape or angular geometry.

Hybridisation of Elements involving d-orbitals

The elements present in the third period contain d orbitals in addition to s and p orbitals.

The energy of the 3d orbitals are comparable to the energy of the 3s and 3p orbitals.

The energy of 3d orbitals are also comparable to those of 4s and 4p orbitals.

As a consequence, the hybridisation involving either 3s, 3p and 3d or 3d, 4s and 4p is possible. However, since the difference in energies of 3p and 4s orbitals is significant, no hybridisation involving 3p, 3d and 4s orbitals is possible.

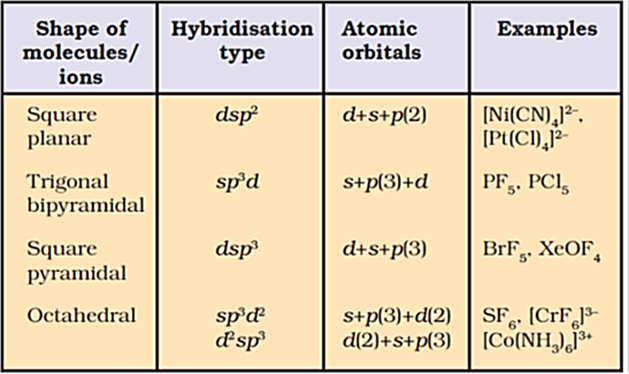

The important hybridisation schemes involving s, p and d orbitals are summarized below:

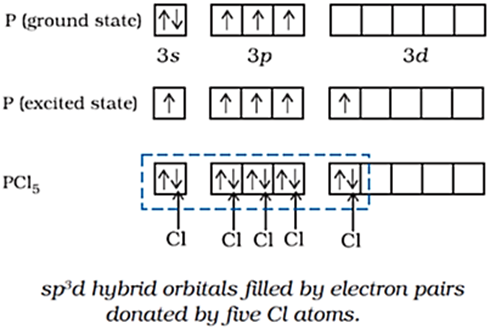

Formation of PCl5 (sp3d hybridisation):

The ground state and the excited state outer electronic configurations of phosphorus (Z=15) are represented below.

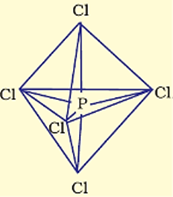

Now the five orbitals (i.e., one s, three p and one d orbitals) are available for hybridisation to yield a set of five sp3d hybrid orbitals which are directed towards the five corners of a trigonal bipyramidal as depicted in the figure below.

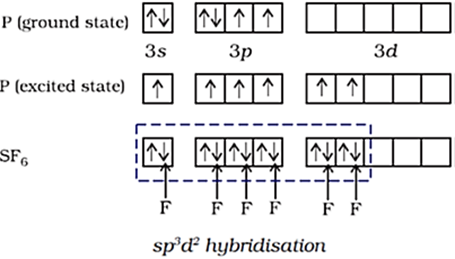

Formation of SF6 (sp3d2 hybridisation):

In SF6 the central sulphur atom has the ground state outer electronic configuration 3s2 3p4.

In the exited state the available six orbitals i.e., one s, three p and two d are singly occupied by electrons.

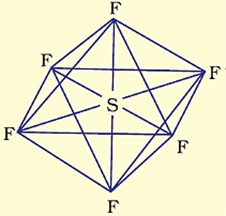

These orbitals hybridise to form six new sp3d2 hybrid orbitals, which are projected towards the six corners of a regular octahedron in SF6.

These six sp3d2 hybrid orbitals overlap with singly occupied orbitals of fluorine atoms to form six S–F sigma bonds.

Thus, SF6 molecule has a regular octahedral geometry as shown in the figure below.

The salient features of this theory are:

(i) The electrons in a molecule are present in the various molecular orbitals as the electrons of atoms are present in the various atomic orbitals.

(ii) The atomic orbitals of comparable energies and proper symmetry combine to form molecular orbitals.

(iii) While an electron in an atomic orbital is influenced by one nucleus, in a molecular orbital it is influenced by two or more nuclei depending upon the number of atoms in the molecule. Thus, an atomic orbital is monocentric while a molecular orbital is polycentric.

(iv) The number of molecular orbitals formed is equal to the number of combining atomic orbitals. When two atomic orbitals combine, two molecular orbitals are formed. One is known as bonding molecular orbital while the other is called antibonding molecular orbital.

(v) The bonding molecular orbital has lower energy and hence greater stability than the corresponding antibonding molecular orbital.

(vi) Just as the electron probability distribution around a nucleus in an atom is given by an atomic orbital, the electron probability distribution around a group of nuclei in a molecule is given by a molecular orbital.

(vii) The molecular orbitals like atomic orbitals are filled in accordance with the aufbau principle obeying the Pauli’s exclusion principle and the Hund’s rule.

Linear Combination of Atomic Orbitals (LCAO)

According to wave mechanics, the atomic orbitals can be expressed by wave functions (ψ’s) which represent the amplitude of the electron waves. These are obtained from the solution of Schrödinger wave equation.

However, since it cannot be solved for any system containing more than one electron, molecular orbitals which are one electron wave functions for molecules are difficult to obtain directly from the solution of Schrödinger wave equation. To overcome this problem, an approximate method known as linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) has been adopted.

Let us apply this method to the homonuclear diatomic hydrogen molecule.

Consider the hydrogen molecule consisting of two atoms A and B. Each hydrogen atom in the ground state has one electron in 1s orbital. The atomic orbitals of these atoms may be represented by the wave functions ψA and ψB. Mathematically, the formation of molecular orbitals may be described by the linear combination of atomic orbitals that can take place by addition and by subtraction of wave functions of individual atomic orbitals as shown below:

ψMO = ψA ± ψB

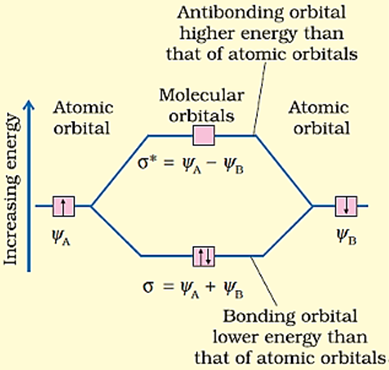

Therefore, the two molecular orbitals σ and σ* are formed as:

σ = ψA + ψB

σ* = ψA – ψB

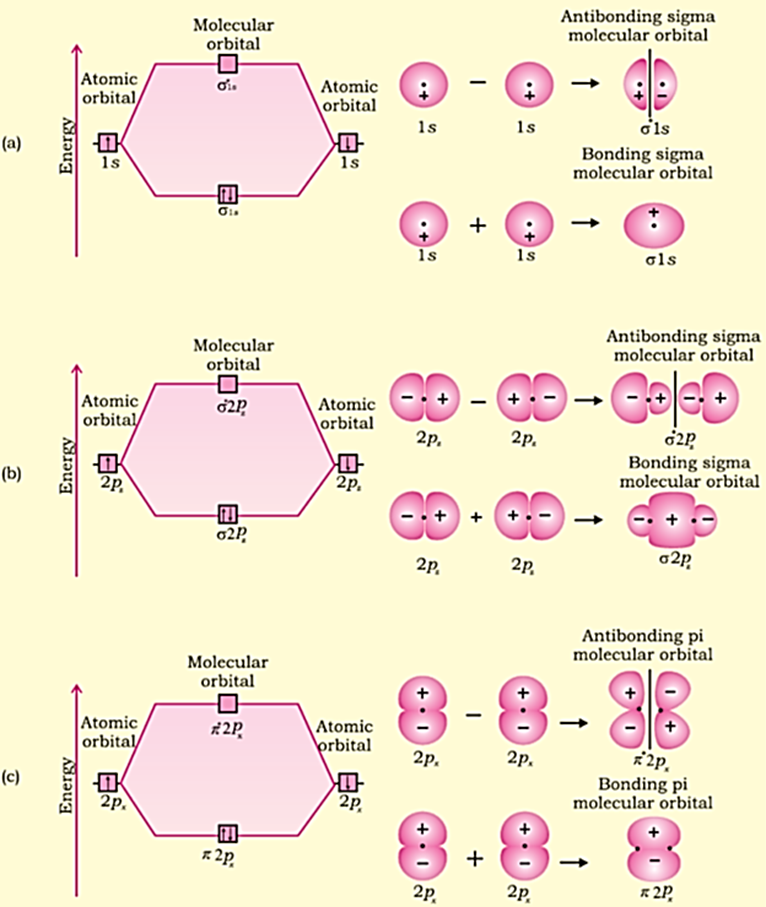

The molecular orbital σ formed by the addition of atomic orbitals is called the bonding molecular orbital while the molecular orbital σ* formed by the subtraction of atomic orbital is called antibonding molecular orbital as depicted in the figure below.

Qualitatively, the formation of molecular orbitals can be understood in terms of the constructive or destructive interference of the electron waves of the combining atoms.

In the formation of bonding molecular orbital, the two electron waves of the bonding atoms reinforce each other due to constructive interference while in the formation of antibonding molecular orbital, the electron waves cancel each other due to destructive interference.

As a result, the electron density in a bonding molecular orbital is located between the nuclei of the bonded atoms because of which the repulsion between the nuclei is very less while in case of an antibonding molecular orbital, most of the electron density is located away from the space between the nuclei.

Infact, there is a nodal plane (on which the electron density is zero) between the nuclei and hence the repulsion between the nuclei is high.

Electrons placed in a bonding molecular orbital tend to hold the nuclei together and stabilise a molecule.

Therefore, a bonding molecular orbital always possesses lower energy than either of the atomic orbitals that have combined to form it. In contrast, the electrons placed in the antibonding molecular orbital destabilise the molecule. This is because the mutual repulsion of the electrons in this orbital is more than the attraction between the electrons and the nuclei, which causes a net increase in energy.

It may be noted that the energy of the antibonding orbital is raised above the energy of the parent atomic orbitals that have combined and the energy of the bonding orbital has been lowered than the parent orbitals.

The total energy of two molecular orbitals, however, remains the same as that of two original atomic orbitals.

Conditions for the Combination of Atomic Orbitals:

1. The combining atomic orbitals must have the same or nearly the same energy.

2. The combining atomic orbitals must have the same symmetry about the molecular axis.

3. The combining atomic orbitals must overlap to the maximum extent.

Molecular orbitals of diatomic molecules are designated as σ (sigma), π (pi), δ (delta), etc.

In this nomenclature, the sigma (σ) molecular orbitals are symmetrical around the bond-axis while pi (π) molecular orbitals are not symmetrical.

For example, the linear combination of 1s orbitals centered on two nuclei produces two molecular orbitals which are symmetrical around the bond-axis.

Such molecular orbitals are of the σ type and are designated as σ1s and σ*1s.

If internuclear axis is taken to be in the z-direction, it can be seen that a linear combination of 2pz - orbitals of two atoms also produces two sigma molecular orbitals designated as σ2pz and σ*2pz.

Molecular orbitals obtained from 2px and 2py orbitals are not symmetrical around the bond axis because of the presence of positive lobes above and negative lobes below the molecular plane. Such molecular orbitals, are labelled as π and π *.

A π bonding MO has larger electron density above and below the inter -nuclear axis.

The π* antibonding MO has a node between the nuclei.

Energy Level Diagram for Molecular Orbitals

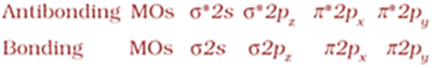

We have seen that 1s atomic orbitals on two atoms form two molecular orbitals designated as σ1s and σ*1s. In the same manner, the 2s and 2p atomic orbitals (eight atomic orbitals on two atoms) give rise to the following eight molecular orbitals:

Contours and energies of bonding and antibonding molecular orbitals formed through combinations of (a) 1s atomic orbitals; (b) 2pz atomic orbitals and (c) 2px atomic orbitals.

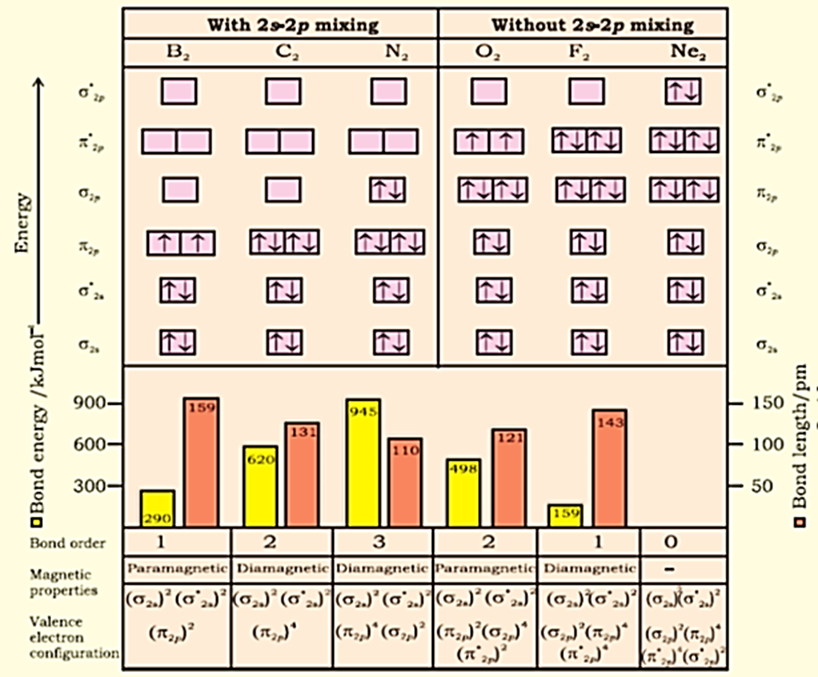

The energy levels of these molecular orbitals have been determined experimentally from spectroscopic data for homonuclear diatomic molecules of second row elements of the periodic table. The increasing order of energies of various molecular orbitals for O2 and F2 is given below:

σ1s < σ*1s < σ2s < σ*2s < σ2pz < (π 2px = π 2py) < (π *2px = π *2py) < σ*2pz

However, this sequence of energy levels of molecular orbitals is not correct for the remaining molecules Li2, Be2, B2, C2, N2.

For instance, it has been observed experimentally that for molecules such as B2, C2, N2 etc. the increasing order of energies of various molecular orbitals is

σ1s < σ*1s < σ2s < σ*2s < (π 2px = π 2py) <σ2pz < (π *2px = π *2py) < σ*2pz

The important characteristic feature of this order is that the energy of σ2pz molecular orbital is higher than that of π 2px and π 2py molecular orbitals.

If Nb is the number of electrons occupying bonding orbitals and Na the number occupying the antibonding orbitals, then

(i) the molecule is stable if Nb is greater than Na, and

(ii) the molecule is unstable if Nb is less than Na.

In (i) more bonding orbitals are occupied and so the bonding influence is stronger and a stable molecule results. In (ii) the antibonding influence is stronger and therefore the molecule is unstable.

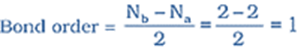

Bond order (b.o.) is defined as one half the difference between the number of electrons present in the bonding and the antibonding orbitals i.e.,

Bond order (b.o.) = ½ (Nb – Na)

The rules discussed above regarding the stability of the molecule can be restated in terms of bond order as follows: A positive bond order (i.e., Nb > Na) means a stable molecule while a negative (i.e., Nb < Na) or zero (i.e., Nb = Na) bond order means an unstable molecule.

Integral bond order values of 1, 2 or 3 correspond to single, double or triple bonds respectively as studied in the classical concept.

The bond order between two atoms in a molecule may be taken as an approximate measure of the bond length. The bond length decreases as bond order increases.

If all the molecular orbitals in a molecule are doubly occupied, the substance is diamagnetic (repelled by magnetic field).

However, if one or more molecular orbitals are singly occupied it is paramagnetic (attracted by magnetic field), e.g., O2 molecule.

Bonding in Hydrogen molecule (H2):

It is formed by the combination of two hydrogen atoms. Each hydrogen atom has one electron in 1s orbital. Therefore, in all there are two electrons in hydrogen molecule which are present in σ1s molecular orbital. So electronic configuration of hydrogen molecule is

H2: (σ1s)2

The bond order of H2 molecule can be calculated as given below:

bonded together by a single covalent bond. The bond dissociation energy of hydrogen molecule has been found to be 438 kJ mol–1 and bond length equal to 74 pm. Since no unpaired electron is present in hydrogen molecule, therefore, it is diamagnetic.

Bonding in Helium molecule (He2):

The electronic configuration of helium atom is 1s2. Each helium atom contains 2 electrons, therefore, in He2 molecule there would be 4 electrons.

These electrons will be accommodated in σ1s and σ*1s molecular orbitals leading to electronic configuration:

He2 : (σ1s)2 (σ*1s)2

Bond order of He2 is ½(2 – 2) = 0

He2 molecule is therefore unstable and does not exist.

Similarly, it can be shown that Be2 molecule (σ1s)2 (σ*1s)2 (σ2s)2 (σ*2s)2 also does not exist.

Bonding in Lithium molecule (Li2):

The electronic configuration of lithium is 1s2, 2s1. There are six electrons in Li2. The electronic configuration of Li2 molecule, therefore, is Li2 : (σ1s)2 (σ*1s)2 (σ2s)2

The above configuration is also written as KK(σ2s)2 where KK represents the closed K shell structure (σ1s)2 (σ*1s)2.

From the electronic configuration of Li2 molecule it is clear that there are four electrons present in bonding molecular orbitals and two electrons present in antibonding molecular orbitals.

Its bond order, therefore, is ½ (4 – 2) = 1.

It means that Li2 molecule is stable and since it has no unpaired electrons it should be diamagnetic. Indeed, diamagnetic Li2 molecules are known to exist in the vapour phase.

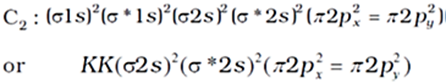

Bonding in Carbon molecule (C2):

The electronic configuration of carbon is 1s2 2s2 2p2. There are twelve electrons in C2. The electronic configuration of C2 molecule, therefore, is

The bond order of C2 is ½ (8 – 4) = 2 and C2 should be diamagnetic. Diamagnetic C2 molecules have indeed been detected in vapour phase.

It is important to note that double bond in C2 consists of both pi bonds because of the presence of four electrons in two pi molecular orbitals. In most of the other molecules a double bond is made up of a sigma bond and a pi bond. In a similar fashion the bonding in N2 molecule can be discussed.

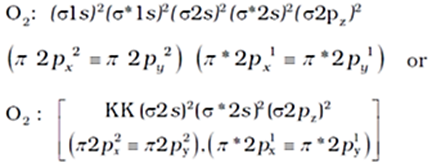

Bonding in Oxygen molecule (O2):

The electronic configuration of oxygen atom is 1s2 2s2 2p4.

Each oxygen atom has 8 electrons, hence, in O2 molecule there are 16 electrons. The electronic configuration of O2 molecule, therefore, is

BO = (8 – 4)/2 = 2

So, in oxygen molecule, atoms are held by a double bond. Moreover, it may be noted that it contains two unpaired electrons in π*2px and π*2py molecular orbitals, therefore, O2 molecule should be paramagnetic, a prediction that corresponds to experimental observation. In this way, the theory successfully explains the paramagnetic nature of oxygen.

MO occupancy and molecular properties for B2 through Ne2.

Hydrogen bond can be defined as the attractive force which binds hydrogen atom of one molecule with the electronegative atom (F, O or N) of another molecule.

(1) Intermolecular hydrogen bond:

It is formed between two different molecules of the same or different compounds. For example, H-bond in case of HF molecule, alcohol or water molecules, etc.

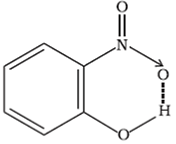

(2) Intramolecular hydrogen bond:

It is formed when hydrogen atom is in between the two highly electronegative (F, O, N) atoms present within the same molecule. For example, in o-nitrophenol the hydrogen is in between the two oxygen atoms.

Intramolecular hydrogen bonding in o-nitrophenol molecule

Online & Classroom Coaching for Grade 6 to 12 & JEE / NEET